Molecular machines can perform tasks such as removing toxins from chaotic environments. But Stoddart’s lab is a haven of tidiness and order. SHyNE spoke to members of his research team at Northwestern University to get know the mentor for whom they work.

Researchers and graduate students working in Lab number 2710 of Northwestern University’s Department of Chemistry know that their boss likes order. He believes tidiness is a culture, an asset for running a successful lab, they note. You won’t find any coats hanging at the back of chairs, bags on the table or boxes lying on the floor. He tells them that if they aspire to be a professor or academician, they need the discipline to bring in funding and satisfy the funders’ expectations.

When newcomers join the lab, they are trained on the lab’s rules for the first few weeks. But the researchers obey the boss out of respect, not fear. Most of them have been following his work for years, yearning to be a part of his team. Once they got in, their respect for their boss deepened. He was unlike any other principal investigator they have ever worked with. His door is always open for them to come talk to him about their concerns.

The boss is Nobel Laureate Sir Fraser Stoddart. Sir Fraser Stoddart was a renowned pioneer in the scientific community before he shot to international fame with his Nobel Prize awarded in 2016 for research on molecular machines with Jean-Pierre Sauvage and Bernard Feringa. The machines have controllable movements that enable them to perform tasks such as snatching up toxins from an environment, making self-repairing materials and targeting the delivery of drugs. The function of the molecular machines will depend on how they are designed. They have tremendous potential – from healthcare and energy to electronics and industry in general.

Stoddart recruits scientists internationally to work in the Stoddart Mechanostereochemistry Group that makes molecular machines. Lorenzo Mosca, a post-doctoral fellow in Stoddart’s group from northern Italy first met him in 2007. The university where he was an undergrad student organized a conference and Stoddart was one of the invited speakers.

“I got the opportunity to drive him around in my small European car,” he says. While showing him around, he took Stoddart into an old building to show him the Borromean rings, a symbol with three interconnected rings used by an aristocratic Italian family as their emblem. Stoddart had synthesized a compound which looks like the Borromean ring in 2004. “I liked his research before and after meeting him, I also liked the person,” he adds. Mosca moved to the United States in 2012 to pursue a post-doctoral fellowship at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. In 2016, he applied to and got accepted at the Stoddart lab to continue his post-doctoral research.

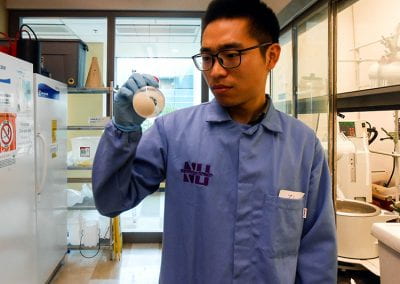

Other scientists seek out Stoddart as well. Chuyang Cheng from the Sichuan province in China is a post-doctoral researcher with an undergraduate degree in chemistry from Peking University in Beijing and a Ph.D. in chemistry.

“I wrote to him saying, ‘I read a lot of your papers and am interested in the research and joining your group and doing some cool chemistry.’ He said OK,” says Cheng. Cheng has worked with Stoddart for six years and knows him better than most of his colleagues. Cheng too works with the molecular machines and had the rare opportunity of accompanying Stoddart to Stockholm for the Nobel Prize ceremony. “It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” he says.

Hasmukh Patel, a post-doctoral researcher from India, is working on an efficient drug delivery system for bipolar disorder and manic depression. He recalls following the Nobel Prize announcement with the zeal of movie fans awaiting the Oscars. He has been following Stoddart’s research since he was earning his Ph.D. in chemistry. “Anyone working in science wants to work with someone who is well known,” he says. Everybody from the lab agrees that the whole day that day was a party.

Magdalena Owczarek, a post doc from Poland, got the first taste of a homecoming parade in the United States when Northwestern celebrated Stoddart’s accomplishment. Stoddart was on one of the floats of the parade waving to everyone. He insisted that his team join him. Owczarek got to wave at the crowd from the float as well. “I haven’t done anything like that before. It was fun,” she recalls.

Stoddart takes his team seriously. He credited them as the main work force behind his prize during the press conference the day he learned about the Nobel. Wherever he was celebrated after that, he made sure his team of researchers accompanied him. The researchers who were not used to the attention were overwhelmed. They insisted that Stoddart should be the first to be photographed, not them.

Once the hysteria surrounding the Nobel died down, things returned to the usual impassioned pace at the lab with one small change. Stoddart used to sit in the conference room inside the lab, read manuscripts left on the table by team members and interact with them regularly. Now he keeps to his main office down the corridor due to new demands for his time. When he is not travelling, he has to attend to a volley of emails inviting him to conferences. “We do not bother him in his main office unless he sends us an email asking us to come,” says Owczarek. Despite the time constraints, the group is still his priority.

The Stoddart Mechanostereochemistry Group has been funded by the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) in Saudi Arabia for the past four years. Saudi Arabia is keen on shifting their economy from oil to other resources, says Patel. The research proposals are designed accordingly. One potential application of the molecular machines can be to harvest energy. Sunlight which is abundant in the Gulf state can be used to trigger the molecular machines to increase the energy content of a compound, solid or liquid. The energy can then be used to produce electricity or heat. Also, some molecules can change shape when light hits them. By changing the shape of the molecule, their energetic barriers can be changed to perform certain functions.

He doesn’t check up on his researchers every day. Instead, he gives them the flexibility and freedom to do their work as long as they bring him good results. He pushes them to come up with solutions to problems on their own. Owczarek who was used to discussing her results right away with her previous boss felt a little lost when she initially joined. But with time, it has made her independent and exhorted her to collaborate with her colleagues.

When Stoddart comes home from traveling, the entire group gathers in the group’s conference room to discuss and provide feedback on the results obtained by three members every Saturday. These meetings are known as the “group therapy”. Each member of the lab gets to present their results every three months. The lab publishes up to 30 research articles every year.

Stoddart knows how to let go of work outside the lab. He invites his whole group to his house during Christmas and Thanksgiving and cooks for them. He lives in a large house on Noyes Street alone since his wife Norma, also a scientist, died after a prolonged battle with cancer in 2004. He prepares traditional Scottish meals with help from his team members. Cheng loves the roast beef he prepares. “We tried to find out how he roasted the beef so well. He said, ‘First you need to have very good meat.’ Then he asked us to guess how much the beef cost. It was $20 per pound!” For Chinese New Year, he asked all the Chinese group members to prepare a Chinese style meal for everyone in the lab. That was the first time Cheng cooked in his house.

Stoddart met Norma as he pursued his Ph.D. at the University of Edinburgh while she was pursuing her undergraduate degree in chemistry. Together, they raised two daughters, Alison and Fiona, both of whom have Ph.D.s in chemistry. Alison lives in UK and is the chief editor of Nature Reviews Materials, an online science journal. Fiona lives with her family in Boston.

“We talk about funny things like jokes when we go to his place,” says Cheng. Sometimes he has difficulty understanding Stoddart’s jokes because he uses old Scottish idioms. “He is very Scottish,” says Margaret Meadows, another post-doc. “He has these really great idioms he comes up with. When we are talking about a research in our group meetings, he always has some story to tell and some Scottish phrase which makes all of us go, ‘wait, what does that mean?’”

Stoddart appreciates art. “He has a ton of art at home depicting scenes of Europe,” says Dr. Margaret Schott, his colleague at Northwestern University. As a boy, he took music lessons at school and enjoyed it very much. He owns a baby grand piano and plays classical music – Liszt, Bach, Beethoven, Chopin. Sometimes during parties, he plays for his guests. The walls of the conference room of the lab are decorated with art depicting chemical structures. “These are all based on the molecules of the systems he has worked on. He has talked about wanting to put up more about the artistic side of chemistry,” says Meadows.